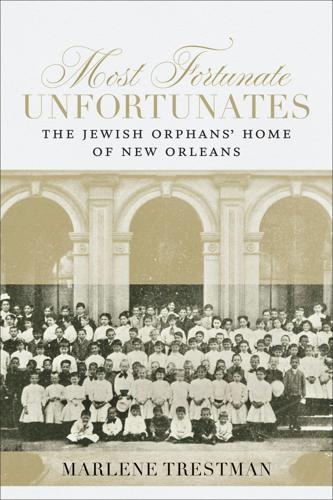

"The Fortunate Unfortunates: The Jewish Orphans Home of New Orleans" by Marlene Trestman; LSU Press, with the assistance of the V. Ray Cardozier Fund and the Mike and Ayan Rubin Endowment for the Study of Civil Rights and Social Justice; 352 pages

What good could possibly come from the recurring deadly yellow fever epidemics in New Orleans during the 19th century?

How could attitudes of rejection and suspicion of Jewish people spawn an institution that has, for almost 200 years, provided incalculable services for Jewish children from many states whose family lives are nonexistent or severely compromised?

The answer lies in Trestman’s exhaustively researched (100 pages of notes and bibliography) yet readable and fascinating account of the founding of a Jewish orphanage and its various eventual correlaries that include the prestigious Isidore Newman School which today serves pre-K through high school scholars regardless of religious and ethnic background.

The author’s special interest in her subject stems from the many services she derived from some of the offshoots of the orphanage, including early day camp and ballet classes at the Jewish Community Center. Later, when Marlene was 11, her mother died and her father became disabled, so the Jewish Children’s Regional Service assigned a caseworker who supervised her foster care provided by the state. The agency also sponsored her attendance at Newman School and upon high school graduation, Goucher College.

The original Jewish Orphans Home was founded by approximately 30 prosperous Jewish men from New Orleans in 1855. The depression, as well as recurrences of yellow fever epidemics, had left many orphaned, and various benevolent societies offered help to them, but not nearly as much as was needed. An orphanage was the apparent answer to the great need, and in 1856, the cornerstone for The Home, as it became known, opened at the corner of Jackson and Chippewa streets.

Through the years, the initial enrollment grew through a coalition with Jewish organizations in other states that offered financial support in exchange for the ability to place orphans in New Orleans.

Trestman develops her story chronologically by recounting the administrations of a series of superintendents, a number of whom have names prominent today in New Orleans civic life.

One of the latter superintendents and one of the most memorable is “Uncle Harry” Ginsburg, who served from 1929 until 1940. His goal was to do away with a set of elaborate rules for all but to respond to each resident as an individual. He wanted each boy or girl to feel like an only child and went so far as to treat each with a birthday party in his apartment, with appropriate refreshments and gifts as one would enjoy if in a private home.

Another superintendent, Isaac Leucht, was an advocate for the establishment of a vocational training component in the orphanage’s educational pursuits. Such a program was for the males, as early on, it was assumed that the female residents would either find work as domestic help upon graduation or would marry. So, although the girls were also given academic opportunities, at age 14 in the early years, they left the classroom to practice homemaking under the supervision of the matrons of the facility. Later, this policy was abandoned and the girls were educated along with the boys.

Significant donors are also mentioned, none more prominent than Isidore Newman, whose generous gesture was owning to his feelings of gratitude for the prosperity the residents of New Orleans had enabled. His only stipulation in making the donation was that “music should be taught there for in all my troubles, music has been a great consoler.”

In addition to his initial gift, Newman continued to make further donations throughout his lifetime and in his will, and his family continues this tradition, Trestman says.

By the early 1940s, the need for the orphanage was diminishing, and in 1944, only 31 orphans were in residence. Fewer applicants, earlier discharges and governmental and community support for families, coupled with increasing costs, made it obvious that the home was becoming unsustainable. One possible measure for continuing its work involved a proposal to merge with a similar Houston facility, but this attempt failed. Aa social worker was hired to oversee the care of residents who could be served in foster homes. By 1946, the remaining six children were all placed in foster homes and the Jewish Children’s Home ceased operation.

In 1960, more than 200 alumni of the orphanage and their family and friends held a reunion, a testament to the gratitude they felt toward the home that had nurtured them or their loved ones in a time of great distress. Long-term or short-term residents testified to the humane manner in which they were provided a good education and a safe and comfortable environment while awaiting, in many cases, the time when they could either be reunited with loved ones or take their place as self-sustaining members of society. Though unfortunate in lacking the security of a home with family, those who lived among the boys and girls and caring staff of the Jewish Orphans Home of New Orleans were indeed fortunate.